By now it had become something institutional. We were at the end of the line, so we wanted to preempt the crisis, by changing our behaviour. I felt the need to no longer see the other artists, my one-time fellow travellers, with whom I had undertaken a journey. I felt the need to try a solitary life, all of my own. I had been passionate about motorbikes for a long time, especially about Moto Guzzi. I had a motorbike, a “Guzzi 500 Alce”, a vintage military motorbike, so there had already been a sign. Setting off, leaving, no longer being in the middle of the artistic paranoia of the roman drawing rooms. I though about the North Cape. I wanted to get to the North Cape with my motorbike. I started to prepare the bike and equipment, studying the 5000km route, the stops, campsites and other technical details. Mentally, I was ready. I wanted to reach the spur of the North Cape, and place on the northernmost point of the planet one of my sticks. The 24th of July, the day of the midnight sun was my aim. I left on the 20th of July. In four days I had to travel 5000km, more than a thousand kilometres a day. But, ten kilometres from Hanover, my motorbike stopped, one of the motor’s valves had broken. It was the morning and I had just started the leg that would take me to Scandinavia. I ended up in a motorbike repair shop. They didn’t have the spare part, so I took the train towards Italy, to get the valve and then back towards Hanover. The bike was fixed, but the rhythm of the journey had stalled and therefore the 24th of July, the day of the midnight sun, was now unreachable. In any way, what I called abstention was already underway. I returned to Rome, passing through Amsterdam and Paris, then towards Italy, through the Brenner Pass and then Venice, and then the “Romea” highway, the motorway towards Perugia and finally arriving in Rome. After a few days with Rosati, I met with Mario Diacono. He had just opened the gallery in Rome. He offered me a show. Like that, unexpectedly. We scheduled it for the 20th of July 1980. I wasn’t convinced, but I did it anyway. I did another in 1983, still less convinced. In the meantime I changed motorbike: I bought a “Guzzi California”, 850cc. The Transavanguardia was in full development. I left again towards Northern Europe, towards Amsterdam. I wanted to see what the gallery “De Appel” and the artistic director Aghi were doing, with whom I had spoken years before about doing a show, which had never come about and had never been given up on. I also wanted to see Marina Abramovic and Ulay there (Marina was a discovery of mine. I met her in 1970 in Rovigno, whilst she was still a student. She was an artist, even if she wasn’t yet one. I offered for her to with me to Comacchio, where I had a house in the countryside, and so she became my guest. I introduced her to Luigi Ontani, the artistic writing of the time, etc., and afterwards she knew how to do the rest extraordinarily). After such a long time I wanted to see her. I left for Amsterdam. I realized straight away just what the “Guzzi California” was, named the “bison of the road” by bikers for its mechanical majesty. The world of motorbikes during the Sixties and Seventies was clearly divided between the ideological image of the European bikes (Moto Guzzi, BMW, Laverda, Ducati) and the Japanese bikes (Kawasaki, Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha). Japanese bikes were rightwing, they were the “nippo-schizzo”, noisy, explosive and fast, and rarely “touring- raid” bikes; in part because they weren’t resistant. They overheated quickly, especially going uphill and when heavily loaded. They shone only in urban settings, in short lines and at motorbike gatherings. The European bikes, in particular Moto Guzzi and BMW, were much more resistant, a bit less explosive and slower, but they had a slightly stronger chassis and were aesthetically more sober. There were two types of riders, rightwing and leftwing, but unlike everything else where there was a clear-cut ideological separation, it wasn’t like that with bikers. The “iron cavalry” really behaved chivalrously. When you passed on the road people greeted each other ritually. If a motorbike had stopped at the side of the road, maybe the rider was just doing his business, everyone would stop to see if everything was ok. I never saw anything different, someone who didn’t adhere to this custom, regardless of the typology or ideology. These things existed only between bikers, between “centaurs”. By this point I was “full time”, and I was a loner. Normally you travelled in groups or pairs, I, instead, was part of the loners, the toughest of all. They could be recognised easily, not only for their two-cylinder Moto Guzzi and BMW bikes, but also for their clothes: jeans with boots, or even trainers, leather jackets with a handkerchief around their necks, and without a helmet or gloves. Instead, their gear was complete: rainproof overalls, a little tent with a sleeping bag, a supply of socks and hardy underwear, tools and spare parts, like cables, inner tubes, lights and the other consumable parts. I am speaking about long distance raid-riders, which I was. The others were known as “schizzatori”, for their short journeys and image. Then there were the women, the “centaur” girls of both types. In passing you wouldn’t realise. You would only see them at the stops and you looked at each other. Their presence was nice. They made the “iron cavalry” more beautiful and erotic. It was a world that made me completely forget art and the paranoia, the ambiguities and nastiness of art.

I liked the girl bikers a lot. They were special women, modern amazons, real, physical. During the quick stretches that lasted more or less 150-200 km I would stop. I drank lots of coffee to stay awake and I would smoke my Tuscan cigar. The rest stops were also the moments of bike-socialising. I was always well looked upon by the other bikers, with my cigar and moustache on show. My bike was too, for its gear and equipment, its large handlebars and particular saddle, with its robust fork and gimbal, more so than other bikes. It was the business. It is not by chance that they called it the “bison of the road”. When I arrived in Amsterdam I went strait to “De Appel”. I wanted to find Aghi, Marina and Ulay. They told me that Marina and Ulay were away, in Italy, in Florence.

Aghi was there. The day after we met at her house. In the past we had been interested in doing a show at “De Appel” that we never managed to realise. We spoke, there was a friendliness or curiosity, or something else, but not enough to embark on a show. They were feminists of the gallery and the programme, and I was a biker with a cigar in my mouth and a “handlebar moustache”; it did not fit together well, even if in part it did fit together strongly.

The day after, at night, Aghi invited me to dinner in a restaurant outside of the city. She was very depressed and unhappy about the death of her friends and partners of the gallery, in that fatal plane crash. After this friendly dinner we did not see each other again. It was 1983.

I returned to Italy, to Florence, where Marina and Ulay were. It was a warm-hearted encounter. She threw her arms around me before I had gotten off my bike, we almost fell to the ground. It was beautiful even though afterwards we retreated into ourselves, in the style of “Marina Abramovic”. I was their guest for two days in a villa at the German Cultural Centre, though nothing happened. She calmly continued her work. She was not very interested in what was going on around her, what was happening to the others. We left each other and I returned to Rome. A short while later I started travelling again. This time I was heading east, towards Yugoslavia, towards Belgrade. I took the motorway of the south towards Bari, from where I wanted to take the ferry, but, getting the day of the boat wrong, I took the coastal road towards Trieste; thousands of unexpected kilometres. Arriving in Trieste, I had to decide whether go through Istria or Slovenia. The weather was nice and I decided to take the Slovenian Alps towards Ljubljana. However, the weather changed quickly, but by that point I was already on the road. Up high, in the mountains, I found strong wind and then rain as well. I arrived in Ljubljana drenched, but I didn’t stop apart from getting a tea. I was hoping that going down the mountain towards Zagreb I would have found nicer weather, but it wasn’t to be. I passed Zagreb without stopping, taking the highway “Brotherhood and Unity”. From Trieste to Belgrade it’s around 700 kilometres, but beneath the rain the bike’s average speed dropped to 60 km/h, so I had to stop 100 kilometres from Belgrade and get a motel. I was exhausted and it was starting to get dark. The day after there was beautiful sunshine. I arrived in Belgrade at 10 in the morning and went strait to the SKC Cultural Centre. I was in my home country, but of my own there was little. Belgrade? What was I doing here? They were still there, the group of critics and artists of the regime, affiliated with the country’s security service. The Museum of Contemporary Art, the Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Union of Artists and the Department of Art History were tightly controlled by this group of zhdanovists (Zhdanov, Stalin’s Minister of Culture, who was always ready to use his gun). They appeared to give me friendly welcoming. They also gave me a date for a show at the SKC gallery. It was 1983. I did this show that didn’t mean anything. Yugoslavia was already moribund. The air was rotten. Belief and faith were by this point subjects of sarcasm and irony.

Nationalisms were on the rise, the ethno-manias and fascisms, within the communist party. I got back on my bike, towards Montenegro, to get the ferry to Bari. By now we were in the autumn of 1984. I had to cross the mountain of Zaltibor, which was already covered in snow, and then follow the mountains of Montenegro. In the early morning, when I started the journey, there was some light rain, but I hoped to find sunshine ahead. Instead, the rain continued and became heavier. I soon realised that the highway that passed through the plains and countryside of Serbia was very dangerous. The asphalt was muddy because tractors and animals crossed it, so I slowed to 50 km/h. It is 600 kilometres from Belgrade to the Port of Montenegro. At the halfway point, I had to break and the bike lost grip. It was a spectacular fall. We found ourselves on the asphalt in a 20- 30m slide. I clung onto the handlebars. The bike was fine, only a broken indicator, whilst I instead felt something wrong with my arm and shoulder. I tried to pick the bike up, but couldn’t. The bike, with the gear, weighed around 300 kilograms, and I only had one arm. In the meantime a tractor was arriving with two farmers, who put my bike back on its wheels. The motor turned on at the first try, so everything was fine, by my left arm was not OK. I could just about move my fingers, and the pain was getting stronger. Yet I managed to operate the clutch and I set off. After an hour on the move I found myself in front of the climb of the famous mount Zlatibor. My shoulder and arm still hurt, and I had no idea what I would find on the mountain road. There was snow, but I hoped the road was clear. I followed in the tracks left by a truck, at walking speed. After a while I overtook it and continued by myself. I was in great pain. I had never been in such a difficult situation on the road: pain, cold and danger. I took the mountain pass and stopped in front of a tavern. I got a tea and a grappa, and then ate something. I could feel that my shoulder was not right. I thought that I had broken something, maybe a tendon or collarbone, but I had to carry on. It was six in the evening and I still had two hours of light. I could do another 100 km and get to a small town with a nice hotel on the road. I set off again. It was a real struggle. After an hour of riding I found rain again. The rain got in my boots, there was water everywhere. No clothing was enough. I still had around twenty kilometres to go. There was a sharp descent, full of hairpin bends, and it was beginning to get dark. These last kilometres were a real struggle to survive. I could see the lights of the town at the bottom and took courage, gritting my teeth. After around forty minutes I finally arrived at the motel. Everyone looked at me as though I was an alien. At the reception they told me that there was no room, but then a free room appeared. They asked me where I came from. They were amazed. I entered the room, but I couldn’t change as even my spare clothes were wet. So I went to the restaurant as I was, to eat something. Then I had a shower, took two aspirin and went straight to bed.

The next day the weather was miraculous: the sun was out and the road was dry. The bike was so dirty that you could no longer pick out its brownish-red colour. It was grey from the thin “film” of mud. I had to travel 150 km to get to the port and it was a wonderful journey after the hell of the previous day. My shoulder was still stiff and painful. The rest of the journey to Rome was routine. I arrived in Rome. My shoulder was less painful so I didn’t go to the doctor. My little studio in Vicolo del Bollo was ever smaller and sadder. I was sleeping in a military camp bed, in a sleeping bag.

This stay in Rome was basically to ready myself for the next trip, which meant, other than the mechanical preparation of the bike, mental and political preparation, because I was returning to Yugoslavia. I had to go back and take part in the “Yugoslav paranoia”, and civil war seemed inevitable to me. Or rather, to tell the truth, I felt a great desire to see what happened to a utopia that had become so dirty and depressing, with the American CIA that had found “Swiss cheese” in Yugoslavia, and what was good, without doubt the heritage of a possible socialist society, that was the social welfare and cultural dialectic of the third world. There was also an interdisciplinary cohabitation of peoples, ethnicities and regions; which by then had all been betrayed, sold and distorted. Yugoslavia was by this point a pathetic and dangerous country. I wanted to return to witness an inevitable and tragic change. The Slavs had never become civilized enough to employ dialectics, sophisms and political skill; and, on the other hand, they had remained attached to their weapons, memories of war and the cult of the canon, the Serbs in particular. During the first journey I had come across an increase in hate and monetary inflation, so it was not hard to imagine the future.

In 1986 I set off again for Belgrade, where I carried out a presence-performance on Tarkowsky’s “mystery of water” at the SKC gallery, and then an interview with Bojana Peic, for the journal “Start” from Zagreb, where she called me “easy-raid”, which meant that she was the only art critic in Belgrade who understood what I was doing. Then I return to Rome again, and this time I parted from my motorbike and Tuscan cigar. I returned straight away to Yugoslavia, to Zagreb, by train with my backpack and sleeping bag. Then I went around all the cultural centres of Yugoslavia: to Ljubljana, Sarajevo, Titograd in Montenegro and then back to Belgrade. During this Yugoslav wandering I met three interesting women: in Sarajevo, Nermina Kurspahic, a theatrologist and director of the gallery “Novi Hram”, with whom I did a show and an important interview; then Luba Gamulin, an art historian and director of the gallery “Sebastian”, with whom I also did an exhibition-performance, with which she closed her gallery; and then Dragica Cakic, philosopher and journalist.

Da 1 a 4

Ilija Soskic, Il mondo è ricco, l’uomo è povero, performance/installazione, calco in gesso della mano, colore verde kent, aculei di acacia, poesie di Velimir Chlébnikov, 1980, Roma, Galleria Mario Diacono (particolari 1,2,3,4).

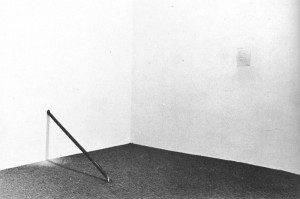

5

Ilija Soskic, Hommage a Malevic, Performance-azione-installazione (legno, rami, stoffa), 1981.

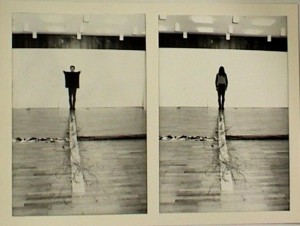

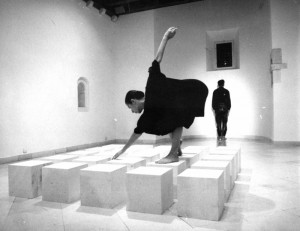

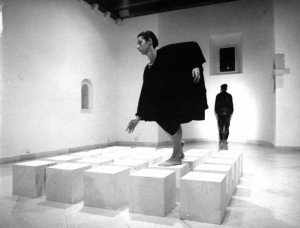

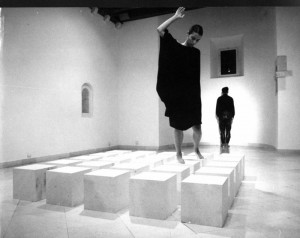

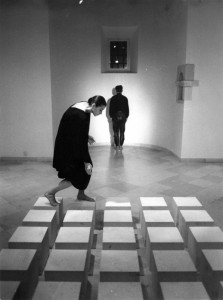

Da 6 a 9

Ilija Soskic, Sator (Carré Magique), Installazione e performance con Lea Tolnai, (marmo e danzatrice), 1989, foto (b/n) Tomislav Svilokos